It’s insane to me that this film turns 20 years old today.

There is nothing more exciting than being a child when a movie like The Lion King comes out. This film has to be one of Disney’s most treasured animated features among the entirety of its cinematic works. And those of us who have seen it know why.

Set in a kingdom of lions in Africa, The Lion King tells the story a lion named Simba, prince of the Pride Lands. When Simba’s father, Mufasa, is murdered by his jealous and treacherous brother Scar, Simba is blamed for Mufasa’s death and banished from the Pride Lands, after which Scar takes the throne. The rest of the film follows Simba as he grows and realizes he must face his uncle and his past, and reclaim his right to the throne.

Jonathan Taylor Thomas and Matthew Broderick voice the young and adult Simba, with James Earl Jones as Mufasa, and Jeremy Irons as Scar.

The film includes an ensemble of other characters: Simba’s best friends Nala (Niketa Calame/Moira Kelly), Timon (Nathan Lane) and Pumbaa (Ernie Sabella); Zazu (Rowan Atkinson); Rafiki (Robert Guillaume); and Scar’s loyal hyenas Shenzi (Whoopi Goldberg), Banzai (Cheech Marin) and Ed (Jim Cummings).

So many elements make this movie memorable, powerful and a classic. Hans Zimmer’s score for one—music that leaves you emotionally hypnotized throughout the film’s most powerful scenes. We are also given a set of songs, courtesy of Elton John, with lyrics so unforgettable that those in their 20s today know them by heart.

Another of the film’s powerful elements is the heartfelt pain that grips you when Mufasa falls to his death and his son desperately attempts to wake him; when Simba is visited by his father’s spirit in a brief, but dramatic exchange; or during the climactic conflict between Simba and Scar atop Pride Rock.

The Lion King fails to fall short in any area of emotional impact, giving us humor, jealousy, love, loss, anger and friendship. Despite using animals as characters, the film’s story effectively makes each character relatable to the audience in some shape or form. No matter how old you are, there’s bound to be at least one part of this movie that brings you to the verge of tears. This is one of many, if not the primary, elements of The Lion King that makes it so powerful, but it’s the whole package that makes it my favorite Disney animated film of all time.

Happy 20th.

“Look at the stars. The great kings of the past look down on us from those stars…So whenever you feel alone, just remember that those kings will always be there to guide you…and so will I.” – Mufasa

Celebrating a legacy

“The goal of this group (was) to do an animated feature from the day I started.” – John Lasseter

Feb. 3, 1986 was a date that would not only impact The Walt Disney Company in less than a decade, but it would forever change the art of animation. But why? What is it that makes this date so significant? Because, friends, Feb. 3, 1986 was the day Pixar Animation Studios started down the path to animation innovation.

Now, for one to commemorate this anniversary the right way, one must tell the story of how Pixar came to be. As I’m sure many are unaware, Pixar’s story begins long before the days of Sheriff Woody and Buzz Lightyear. Believe it or not, the individual truly responsible for Pixar existing at all is George Lucas.

George Lucas in 1983

Lucas’ ambitions and vision of “a galaxy far, far away” led to the formation of Lucasfilm Limited, LLC, Lucas’ production company, and its visual effects division, Industrial Light & Magic.

Pixar’s inception was Lucas’ recruiting Ed Catmull in 1979 to head Lucasfilm’s Computer Division, and the founding of The Graphics Group within the division. TGG’s primary purpose was to explore and develop computer graphics for film.

John Lasseter came to work for TGG in 1983 where he assisted with the short film The Adventures of André & Wally B.

While only two minutes long and incomplete, The Adventures of André & Wally B. demonstrated the potential for computer animation when TGG presented it at SIGGRAPH (Special Interest Group on GRAPHics and Interactive Technologies), an annual computer graphics conference, on July 25, 1984. According to Pixar’s website, the short film’s highlights were the use of complex visible characters, hand-painted textures and motion blur, ground-breaking technology at the time.

Lasseter’s work on the short film and other TGG projects landed him a full-time position as an interface designer that year. However, everything changed for TGG in 1986.

The Pixar Image Computer

Despite TGG’s success in harnessing computer graphics, and putting them to use in sequences such as the stained-glass knight in Young Sherlock Holmes (1985), Lucasfilm was suffering financially. Lucas’ 1983 divorce and declining Star Wars license revenues after Return of the Jedi’s (1983) release were contributing factors to this financial crisis. As a result, TGG split from Lucasfilm, where it became a lone corporation called Pixar, named after the Pixar Image Computer used by TGG in its time with Lucasfilm. Catmull stayed with Pixar, becoming the company’s president.

Months after his May 1985 departure from Apple, Inc., Steve Jobs saw this split as an investment opportunity. He proceeded to purchase Pixar’s technology rights from Lucasfilm for $5 million. All purchase and stock pricing agreements between the two companies officially closed Feb. 3, 1986.

Steve Jobs in 1987

Now, we’re aware of Pixar’s legacy in film and animation today, but following Jobs’ investment, Pixar was primarily a computer hardware company. The primary product was its namesake, the Pixar computer, and one of the buyers of Pixar computers just happened to be Walt Disney Studios. At the time, Disney used the computer as a part of their CAPS project (Computer Animation Production System) to digitally paint the cells of 2-D animated films. The studio’s first film to utilize this process was The Rescuers Down Under (1990).

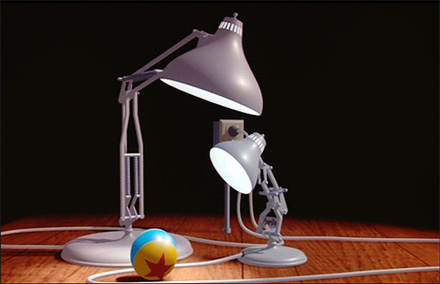

While marketing and selling Pixar computers, Lasseter and the other Pixar animators were continuing to advance computer animation techniques. From 1986 to 1989 Pixar created four computer-animated short films, two of which made history for Pixar. They were Luxo Jr.(1986), Red’s Dream (1987), Tin Toy (1988) and Knick Knack (1989).

Luxo Jr. became the first computer animated film to receive the nomination for Best Animated Short Film at the 59th Academy Awards (March 30, 1987). Tin Toy became the first computer animated film to win the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film at the 61st Academy Awards (March 29, 1989).

Despite Tin Toy’s achievement at the Oscars, Luxo Jr. made the bigger impact; more so than any other short film in the company’s history for that matter. If it weren’t obvious enough, the short film’s title character became the infamous hopping lamp we all see in the Pixar logo sequence. The featured desk lamp has become synonymous with Pixar, and vice versa. I like to think of Luxo Jr. as the Steamboat Willie (1928) of Pixar. In that sense, we can all guess what Pixar’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) equivalent is…but I’ll get to that in a minute.

By 1990, sales were down for Pixar and Jobs had invested so much money at this point he practically owned the company. Pixar sold its hardware division to Vicom Systems in April 1990, and took on a larger role as a production company by using its computer animation for commercials.

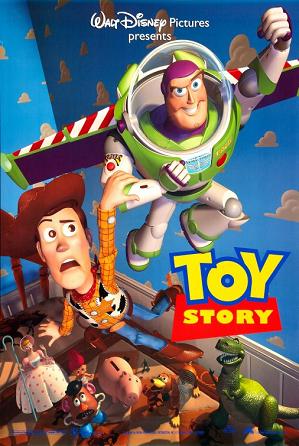

1991 became the year that would change everything when Disney contracted Pixar to produce three computer-animated feature films. The first of these was, of course, Toy Story (1995).

Technologically speaking, producing an 81-minute computer-animated film was a huge step for Pixar. Not only because they hadn’t ever done it, but also because nobody had done it at this point. The story-writing process came as a bit of a struggle too.

Lasseter and his creative team began tweaking the film’s story to the recommendations of Disney executives, but the film’s first executive screening proved unsatisfactory. In fact, it was a huge letdown. Disney then attempted to shut down production and relocate Pixar to Walt Disney Studios to have more control over the film. Lasseter, as a last resort, pleaded for one more shot to do the film Pixar’s way. The executives granted Lasseter’s request, after which he and his creative team initiated an entire rewrite from scratch. In just two weeks, Pixar delivered the concept for the Toy Story we have today.

Toy Story hit theaters Nov. 22, 1995, was met with critical acclaim and made $191.7 million in its initial U.S. run from 1995-1996. To date, it is the sixth-highest rated film of all time on Rotten Tomatoes with a 100% rating based on 77 reviews. Its sequel, Toy Story 2 (1999), is Rotten Tomatoes’ highest rated film with a 100% rating based on 162 reviews.

The Big Four: (left to right) Joe Ranft, Pete Docter, John Lasseter and Andrew Stanton in the early 1990s.

I would never take credit away from the collection of animators, writers, producers and actors that brought Toy Story to life. but I feel the need to emphasize the significance of these four individuals. Without them, the concept of Toy Story we know and love today probably wouldn’t be. Their passion and imaginations pushed Pixar’s creative team to make the company what it is.

Sadly, Ranft died in a car accident on California State Route 1, Aug. 16, 2005. In addition to his story-boarding and concept work with Pixar, Ranft voiced characters in the first seven Pixar films. His funniest, and probably most memorable role is Heimlich the caterpillar in A Bug’s Life.

“”Yes, we worry about what the critics say. Yes, we worry about what the opening box office is going to be. Yes, we worry about what the final box office is going to be. But really, the whole point why we do what we do is to entertain our audiences. The greatest joy I get as a filmmaker is to slip into an audience for one of our movies anonymously, and watch people watch our film. Because people are 100 percent honest when they’re watching a movie. And to see the joy on people’s faces, to see people really get into our films…to me is the greatest reward I could possibly get.” – John Lasseter on Toy Story’s impact

Theatrical release poster

Toy Story was nominated for three Academy Awards in 1996, unfortunately not Best Picture, and the award for Best Animated Feature wasn’t created until 2001. The film did receive nominations for Best Original Screenplay, Best Original Song (“You’ve Got a Friend in Me”) and Best Original Musical or Comedy Score. Although Toy Story didn’t win any of the three, John Lasseter was presented with a Special Achievement award.

Toy Story’s success added Pixar to a long line of historical achievements in the film industry. Because of Toy Story, the world saw that the sky was the limit with animation, and with that, the future held a place for many extraordinary animated titles, many of which were products of Pixar.

A major shift in ownership took places in 2006 when The Walt Disney Company bought Pixar for $7.4 billion. This transaction was the result of years of disputes between Jobs, Pixar’s majority shareholder, and then Disney CEO Michael Eisner. Since the production of Toy Story 2 in the late 1990s, disagreements regarding Pixar’s three-film contract arose, as Toy Story 2 was originally planned for straight-to-video release. When Pixar moved the film up to a theatrical release, Disney still refused to include it as a contract commitment.

With further disputes over story and sequel rights, as well as division of labor and profits, Jobs announced Pixar would seek distributors outside of Disney. Obviously, this never happened.

Negotiations resumed following Eisner’s September 2005 resignation as Disney’s CEO; replaced by Robert Iger, Disney’s current CEO. It was after Eisner’s resignation when negotiations for Disney’s acquisition of Pixar began, completing May 5, 2006. Many of Pixar’s earliest animators and creative team members are now executives running the company, including Lasseter as Pixar’s CCO. Catmull still retains his position as president.

The buyout officially ended Pixar’s 20-year reign as an independent production company, making Cars (2006) its last independent feature. To me, as a viewer, this means the seven true Pixar films will forever be Toy Story, A Bug’s Life (1998), Toy Story 2, Monsters, Inc. (2001), Finding Nemo (2003), The Incredibles (2004) and Cars.

Of course, even as Disney is credited (by word-of-mouth) with destroying Pixar’s legacy by having control over the company, Pixar still released critically and commercially successful films since the buyout. The list of films since Disney’s acquisition includes Ratatouille (2007), WALL·E (2008), Up (2009), Toy Story 3 (2010), Cars 2 (2011), Brave (2012) and Monsters University (2013).

Most of Pixar’s films since Disney’s purchase contain heavier themes, particularly Up, which explores love and loss in a way audiences probably didn’t expect upon their first viewing. With the exception of Cars 2, I would say all of Pixar’s films have matured since the company’s joining Disney. Although, the transition toward a mature tone really began with Toy Story 2, and of course, I’m referring to Jessie’s recounting of enduring abandonment at the hands of her owner Emily.

In the future, Pixar plans to release Inside Out (2015), a journey into the human mind; The Good Dinosaur (2015), a film probably similar to Disney’s Dinosaur (2000); and Finding Dory (2016), the highly-anticipated sequel to Finding Nemo.

Pixar’s studio in Emeryville, Calif.

As Pixar approaches its 30-year anniversary in 2016, one can only reflect upon the mark the company has left, and continues to leave, on the film industry.

From astonishing short films and an ambitious feature-length project to becoming the world’s pioneer in computer animation, Pixar continues to dazzle filmgoers and animation enthusiasts. And if the company’s impeccable ability to tell a story means anything, it’s that no matter what happens, the legacy of Pixar will be with us forever.

Disney’s Savior and Forgotten Past

The Walt Disney Company is known for extending its reach as a media conglomerate with its acquisition of Marvel Entertainment, LLC and Lucasfilm Limited, LLC, but every business has its horror stories.

According to an Oct. 30, 2012 press release, Disney purchased Lucasfilm for $4.05 billion exactly one year ago next month. While it is true Disney retains a powerful hold over the entertainment industry today, Disney faced financial ruin six decades ago; a forgotten part of Disney history in contemporary society.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) was the first animated feature-length film Disney produced, and the first in the history of film. It was a commercial and critical success, earning $6.7 million by May 1939, and set the bar for future animated productions.

Pinocchio (1940) was Disney’s next feat in feature-length animation. Critics lauded the film for its accomplishments in animation and storytelling, and it presented Disney with its trademark theme, “When You Wish upon a Star.” However, contrary to what many may think, Pinocchio didn’t break much of a profit upon its initial release. The film was only shown in English, Spanish and Portuguese, while Snow White played in 49 countries in 11 languages. Earning only $2 million overall, Pinocchio made $1.2 million for Disney after a $2.7 million investment.

Disney’s third feature, Fantasia (1940), was even more of a financial failure, initially earning only $325,000. This film never even left the U.S. due to the special sound equipment required for screenings, provided only by RCA at this time. The reason for this was that Fantasia was the first commercial film to be shown in stereophonic sound. The theaters of the time simply weren’t fitted with the presentation tools necessary for stereophonic sound. This, unfortunately, can be the cost of innovation. Disney showed the film in select theaters, after which receipts proved a wide release to be impractical.

Now what was the reason for this major financial loss one might ask? The answer is World War II. The war closed off the European market to the western world, so the majority of international revenue was unavailable to Disney at this time.

Dumbo (1941) and Bambi (1942) were already in production during the war’s early years. Dumbo turned out to be the only successful film during World War II due to its short running time of 64 minutes and simple story, but there was also another reason. Two months after Dumbo’s release, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, thus marking the beginning of America’s entrance into combat with the Axis Powers. As a result, success for Bambi became impossible. Even with a portion of Bambi scrapped to save on production costs, the film still only earned the studio $1.6 million after a $1.7 million budget.

The war affected Disney in more ways than just weakening Bambi’s release. Many of the studio’s animators were drafted, and those who weren’t had to contribute time to producing propaganda cartoons. Because the company’s founder, Walt Disney, was forced to rely on government funds for the sake of his studio, the propaganda cartoons were the government’s compensation. One of the government’s key interests at this time lied with South America due to potential ties with Nazi Germany. The U.S. wanted to promote relations with Latin America, as well as keep Latin American theaters from showing films associated with the Axis Powers.

These conditions, along with many unfinished story ideas from the past several years, brought viewers the “Package Film Era” of Disney features. Six films released from 1942 to 1949; Saludos Amigos (1942), The Three Caballeros (1944), Make Mine Music (1946), Fun and Fancy Free (1947), Melody Time (1948) and The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949).

The Disney Package Era

These films were short in running time and cheap to produce, some even blending live-action elements for the sake of using as minimal animation as possible. The majority of the animation used was mostly produced using live-action reference techniques, such as rotoscoping.

Of these six films, the two better-known parts today are probably Ichabod and Mr. Toad’s adaptation of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, and the “Peter and the Wolf” segment from Make Mine Music.

Neal Gabler’s book, Walt Disney: A Triumph of the American Imagination, recalls that at this time, “the famous Disney touch had become cloying.”

The package films were not major box office successes, but their earnings did help finance Cinderella (1950). Cinderella marked the return of a single-narrative animated feature format, the first film since Bambi to do so. Because of the company’s gathered debt following World War II, pursuing a full-length animated feature like Cinderella became a risky endeavor.

This time, of course, the odds played out in Disney’s favor, both Walt and the studio. Cinderella was a huge box office success, earning $7.9 million after a $2.2 million budget; the studio’s first commercial hit since Snow White in the late 1930’s. Box office revenue combined with merchandise, such as vinyl albums and publications, made it possible to produce Alice in Wonderland (1951), Peter Pan (1953) and Lady and the Tramp (1955), as well as invest in live-action titles. Cinderella’s success also gave Walt adequate finances to establish his own distribution company, giving birth to the Buena Vista Distribution Company in 1953, known today as Buena Vista Pictures Distribution.

Peter Pan was the last Disney animated feature released through RKO Pictures, Disney’s distribution source since Snow White. Since Lady and the Tramp, every Disney animated feature has been released through Buena Vista.

What all this means though, is that the Disney company’s survival and power today is primarily attributed to the success of Cinderella.

“The failure of [Cinderella] would have sunk the Disney studio,” Gabler wrote. “[Instead, it] wound up rescuing [the studio] from financial disaster and spiritual despair.”

Who knows for sure what would have been without Cinderella. Yes, the Disney company has invested just as much into live-action filmmaking as animation today, but I think we can all agree that animation is the heart and soul of the Disney studio. Had Cinderella flopped, would we have The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992) or The Lion King (1994)? Again, who knows for sure.

What we do know is this: Disney animation lives on because of Cinderella, making it one of the most important animated films in the company’s history.

Disney hasn’t always been such a global force in the entertainment industry, and this dark period of financial crises shows that. The company can plummet today, no matter how unlikely, just as they almost did 60 years ago.

Disney’s studios certainly churn out some crap flack every once and a while, but occasionally they do get it right and give us something we cherish for the rest of our lives.